Interview with Atul Gawande, MD

Aubrey Calo

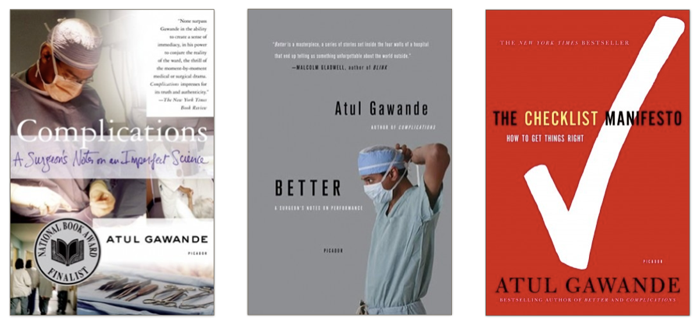

Aubrey CaloAtul Gawande, MD, is a general and endocrine surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital; professor at Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Public Health; executive director of Ariadne Labs; co-founder and chairman of Lifebox; author of Complications (2002), Better (2007), and The Checklist Manifesto (2009); and staff writer for The New Yorker. thirdspace talked to him about his life as a medical student, resident, surgeon, and award-winning writer.

What was it like for you to be a student at Harvard Medical School (HMS)?

It wasn't so bad. We had the afternoons off. That wasn't the experience of most of my friends who were in medical school elsewhere. By comparison, I thought we had it a little bit easier, a little bit better.

How did that environment affect your medical education?

I liked the freedom--it let me work in the lab. I tried basic science, and a variety of different things, before figuring out where I wanted to focus. I'd come from having worked a few years elsewhere, so it was great to be back at school, building skills and knowledge again.

What is your most memorable experience from those four years?

Aside from the Second Year Show...

Did you perform in the Second Year Show [HMS’ annual student parody]?

I did, and thank goodness it wasn't videotaped back then, because I was dressed up in drag. There are so many memories: talking to Ron Arky, a faculty mentor of mine, for an hour about nothing in particular; arguments in class about whether a professor was being politically incorrect or not; doing the dog lab, which was controversial but also really interesting…

What was the dog lab?

We catheterized and ultimately euthanized dogs as part of our training in cardiac physiology.

How did you feel about that?

From a surgeon’s perspective, we see very little trauma. The best learning experience I had in trauma was a pig lab during residency where we went through 18 different injuries that were made to a pig. We had to learn how to repair each injury, and then euthanize the pig. As a surgeon, I still use what I learned in that lab with a pig, fourteen years ago. Whereas for the dog lab, I don’t know how much we really got out of it. My dog died in the very first maneuver, so it was pretty unsuccessful because I didn’t learn anything. My dog died within about fifteen minutes.

Was that a sad experience for you?

Sad, of course, but also frustrating, because the only justification for doing that to those animals was that we would learn things we would use forever. Since I didn’t, it seemed like a complete waste. Clearly, you’re not doing the dog lab anymore. I think people concluded that it was not in good cause.

I understand that you started writing during your residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. You didn’t have any previous writing experience, is that right?

Yes. During my second year of residency, a friend of mine was a part of the group that started Slate magazine. It was 1996, back in the days of the Netscape browser. I had not written before for a public audience in any significant way, so I wasn’t a natural person to be a writer for their new magazine. But nobody wanted to write for them because - you know, who’s gonna read on the web? That was the argument back then. So, they asked their friends to write. I got lucky. They asked me and I said, Sure, I’ll give it a try.

Was it a steep learning curve?

Well, my first articles were not very good at all, but the team at Slate were fantastic editors. Editing, I learned, is really like coaching. The best editors help you get better at what you do. They would tell me, “You need to make it more vivid. I can’t see what it’s like to look at an EKG,” or “I can’t smell what it’s like when you’re in that room. Give us that,” “This other section is blah.” And they’d pick apart my reasoning. They’d say: “You know, sounds like a weak argument.” It was great experience. I did about 30 columns for them, what we’d call a blog now, and they grew tremendously during that time. Over a year and a half they went from 300 hits per article to 300,000 hits per article. I got the advantage of that audience and among the folks who were following the column was a New Yorker editor who asked if I’d write something for them.

(Excerpt from Complications: A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science)

How old were you when you were asked to write that article for The New Yorker?

I was late to medical school. I did about 5 years away, so I was 33 at that point.

How did it feel? Was it terrifying, because it’s THE New Yorker?

You know, everything is terrifying at a distance. I turned in the first draft and they told me I had to rewrite it. I always hated rewriting, but I rewrote it. And then they told me I had to rewrite it again. And then they told me I had to rewrite it again, and again, and again…22 rewrites. The terror disappeared after the first rewrite. After that it was just painful. But, the thing I had to admit was that every time they’d push me to do another rewrite, it just kept getting better, and they’d keep identifying things that could make it better still. I had started with two main stories that were intersecting, and by the time it was done, one of them had completely disappeared, and the other moved from the beginning to the end. It was a good experience, even though it was painful.

It must have been frustrating to keep getting it back. What made you persist in rewriting?

It was the thought that as long as they were interested in me, I had a shot at getting into The New Yorker. But, I needed to make it good enough to get in. Discovering that they weren’t giving up on me was reason enough to keep going. But it took 10 months, and I didn’t know if it would ever end.

Did your writing influence your work as a physician?

At any given moment, I don’t think so. When I’m with a patient, I’m not really thinking: “Could this person be a New Yorker story?” It’s much more that writing gave me space to sit back and reflect on what might be an interesting issue. It gave me an excuse to be able to do things I wouldn’t ordinarily do. In that first article for The New Yorker, I started out of wondering if you could replace a doctor with a machine. I was thinking about a set of studies that had looked at doctors diagnosing chest pain and whether machine could do it better, and puzzling over what that really signified. Writing gave me a reason to dive in deep and think about it hard, to go visit a place like a hernia hospital that does nothing but hernias up in Canada. The magazine put me on a plane and sent me there. Writing puts me in a habit of constantly reflecting on my practice and issues that we deal with day-to-day. It’s given me a set of habits that have led to our laboratory researching health systems improvement and helped me avoid burnout. It makes me pull up from the routine frustrations of medicine, and ask, Why is it always this way? Does it have to be this way?

It sounds like writing really gave you the chance to explore.

Yes, as a physician you end up having to specialize more and more as time goes on, whereas what attracted me to medicine is that I have a wide array of interests. Part of the attraction of being a surgeon, oddly enough, was surgical residency where you get to do everything: neurosurgery, trauma, intensive care, cardiac; I had to take care of the diabetics, I had to take care of the kids. I loved the fact that there wasn’t any part of medicine I wasn’t going to see, but the reality of practice is that you get just one little tiny vantage point. So, it would be easy to burn out, I think, if I didn’t have another connection. That might have been science. It turned out to be writing for me.

Would you advise students to have another outlet as well, a creative pursuit or something else they’re interested in?

I think it varies a lot personality to personality. For some people, really mastering an art and making that what you do is wholly satisfying in and of itself. For other people, it’s using medicine to recognize problems, and they love being in the laboratory and trying to solve those problems. Then, in a funny way, the patients are a relief from the trials of a laboratory. In medicine, the key is finding where you’re going to be successful, happy, and effective in what you do, and not let yourself burn out. I think much more important than doing something creative on the side, is finding a place where you’re actually happy with the people and the system you are working in. There was a great study by the AMA and the RAND Corporation looking at burnout among physicians. Being in a place that had a high quality of care, good systems, and people you liked working with was a much higher indicator of whether physicians avoided burnout.

What is the most difficult lesson you’ve learned about writing that you can pass onto aspiring authors?

It’s the same thing I found difficult about medicine: the level of detail that matters is always deeper than you think. In medicine, it’s really knowing the eighth item in the past medical history, really completing the review of systems, really knowing every single medication, really noticing that laboratory value that you were inclined to ignore--there’s no level of detail that turns out not to matter. It’s much the same in writing. The effort to rewrite, to keep poking and to pay attention to every detail, every word, is either painful or rewarding. In medicine or in writing, it’s all about the details, and whether you are willing to go to that level of detail or not.