Interview with Abraham Verghese, MD

Jason Henry

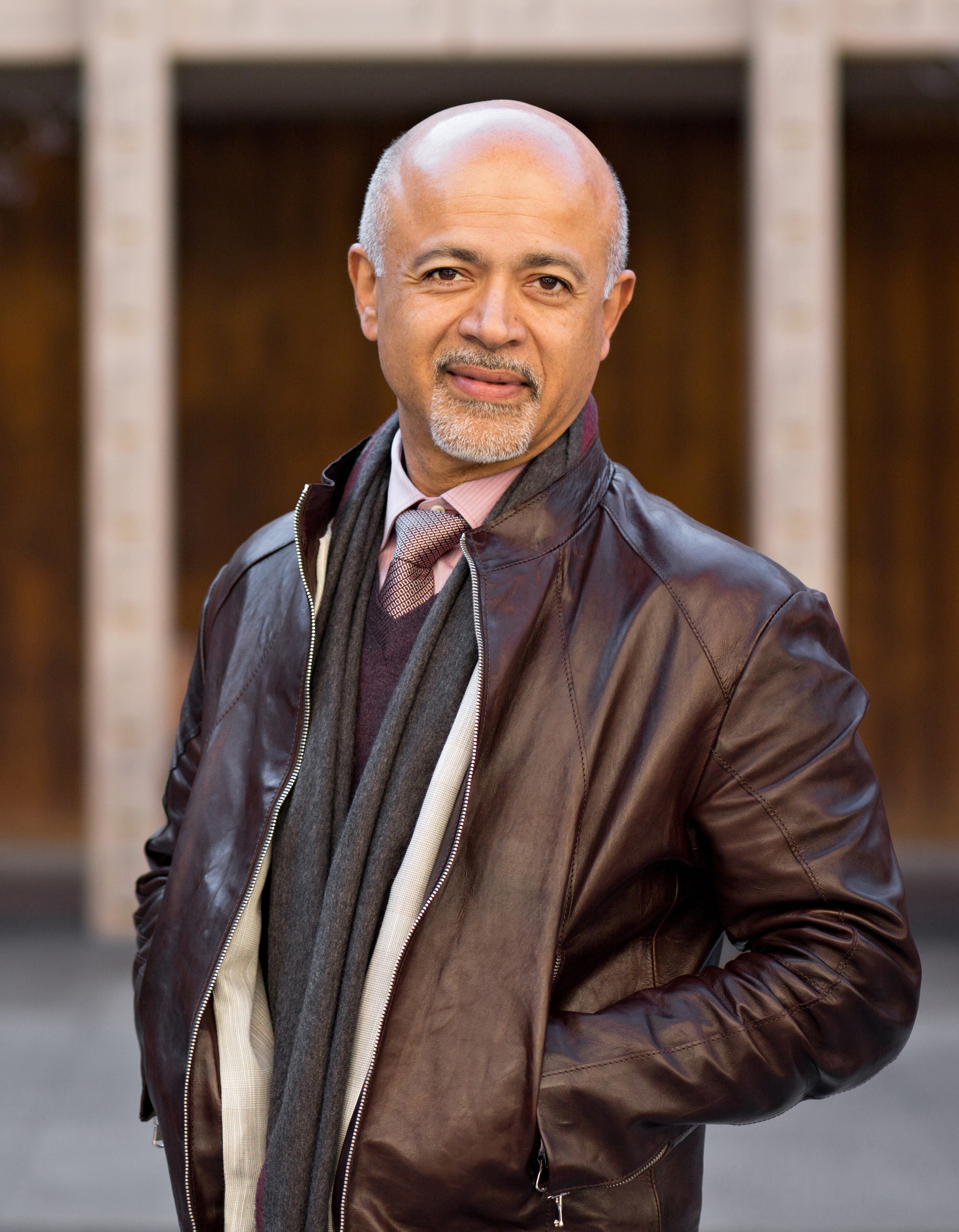

Jason HenryAbraham Verghese, MD, is a New York Times bestselling author, a world-renowned expert in physical diagnosis, and Vice Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine at Stanford University. Trained in internal medicine and infectious diseases, Dr. Verghese received the National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama for "reminding us that the patient is the center of the medical enterprise." We sat down to speak with him about his views on literature, medical education, and what binds the two together.

Where does the story of your life begin?

In Africa. I was born and raised in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. My parents were physics teachers from India.

Did you complete your education in Ethiopia?

Unfortunately, no. In my third year of medical school, a very harsh military government took over the country and closed the medical school. They sent all university students to the countryside to educate the masses, and expatriates were asked to fend for themselves. I think they wanted to get the intellectuals out of town. There was a lot of violence. Many of my medical school classmates became guerrilla fighters, and one eventually became Prime Minister of the country some 20 years later—Meles Zenawi. Several were tortured or killed or died fighting the regime.

Was that when your family immigrated to the United States?

Yes. We ended up in New Jersey. However, I wasn't able to pick up where I left off at school. As is the case in most of the world, my medical school was a 6-year program straight out of high school. Since I was forced to leave the country mid-way through my schooling, I found myself in New Jersey with not as much as an undergraduate degree.

That must have been a painful setback. How did you recover?

I started working as an orderly, first in a nursing home and then at a hospital near my home. And I didn't find this way of life disappointing. I was free and earning money. I was able to buy food, and even a car. It was a great life. For a time, I thought that was going to be my destiny. Then one day I saw Harrison’s textbook of medicine lying on a desk on the ward. I loved that book and I knew it pretty well. Seeing it reminded me of all of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology I had learned, the patients I had seen, and I had an epiphany that I must finish medicine.

You received your medical degree from an Indian medical school.

Yes. Since I wasn't able to continue my education in the United States, I looked for alternative ways. I had an aunt in New Delhi who helped me apply for admission as a displaced Indian citizen. I got admission to the third year of a five year medical program at Madras Medical School.

What did you like the most about medical training in India?

The fact that it was focused, just as it was in Africa, on bedside medicine—mining the body for clues. I find it a bit ironic that my reputation in medicine, such as it is, the reason I am at Stanford and perhaps invited to Harvard to teach – is because of the stuff I learned as a medical student in Madras! When I teach the art of physical diagnosis, I catch myself using the same phrases that my professors taught me in medical school. For example, I repeat: “Don’t try to palpate the spleen. Let the spleen come and palpate your fingers.” Because spleen is hard to feel; it’s not hard like the liver. It’s a soft, mushy organ. I’ve used that phrase thousands of times! Passing on knowledge that my teachers passed onto me seems like celebrating the Eucharist. There is true joy in that ritual and all rituals are about transformation.

"That tube is the Devil's own instrument. If you gave me all of Haile Selassie's riches, I'd still say no to that tube."

I took my own deep breath. I sat on the edge of his bed. I held his hand. "Mr. Walters, I'm afraid I have some bad news. We found something unexpected in your belly." This is the first time in America that I had to give someone news of a fatal illness, but it felt like the first time ever. It was as if in Ethiopia, and even in Nairobi, people assumed that all illness--even a trivial or imagined one--was fatal; they expected death. Those things that you couldn't do, and those diseases you couldn't reverse, were left unspoken. It was understood. I don't recall an equivalent word for "prognosis" in Amharic, and I'd never tried to speak to a patient about five-year survival or anything like that. In America, my initial impression was that death or the possibility of it always seemed to come as a surprise, as if we took it for granted that we were immortal, and that death was just an option."

(Excerpt from Cutting for Stone)

Where did you complete your residency training?

I went to residency at East Tennessee State University, in Johnson City, and then to Boston University School of Medicine for my fellowship in infectious diseases.

Your first experiences working as an infectious diseases physician in Tennessee had a profound impact on you. Can you tell us a bit about that?

I worked in Tennessee for 5 years treating people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. No one expected to find an HIV outbreak in this small area of the South. I was struck by the number of patients we had. It was a phenomenon of migration: young gay men who left home quietly to live in a big city were returning home to die. It was tragic. We didn't have any HIV treatment then. I was doing it all, getting quite burnt out but also quite transformed by the experience and had an impulse to tell this truly American story of migration that I had the honor and misfortune to witness.

How did you get started with writing?

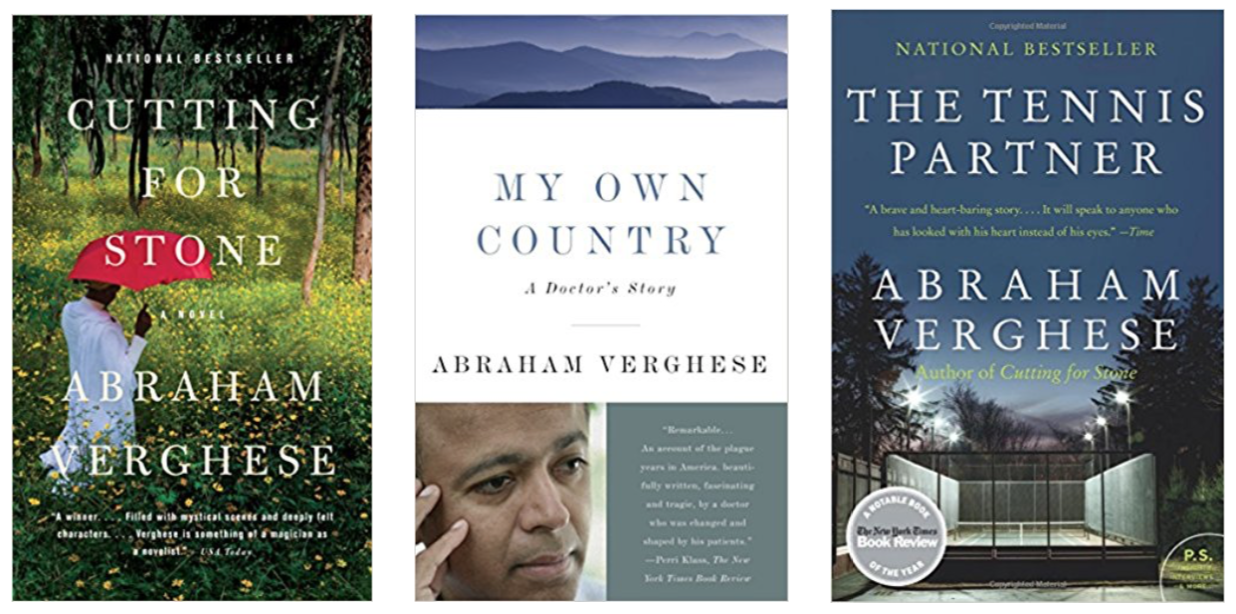

Prior to completing my fellowship in infectious diseases, I only wrote scientific papers in medicine and a few essays in the Annals, in columns such as On Being a Doctor, and Other End of the Stethoscope. But writing those was easy -- they weren't literature. I wanted to be a fiction writer, because I loved fiction. I applied and got accepted to the Iowa Writer's Workshop. It was there that I wrote a short story called Lilacs, that ended up being published by The New Yorker. I thought that this was my big break. But the editors from New York wanted me to write a nonfiction essay about AIDS in rural America. They never took the piece—the editor changed, and I wrote other things for the new editor, Tina Brown—but that essay led to a contract to write a nonfiction book. I had to learn to write nonfiction. I started to read work that I thought I could use as a model.

Is there a particular book you read back then that influenced your future writing style?

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell. So many others. Didion. Capote. It made me more willing to put myself in the story. That became a method in my writing. I wrote from a point of view of how the story was affecting me, becoming a character in some sort of a way. But I always found that hard, longed to get back to fiction.

Self-disclosure is often a scary aspect of writing for medical students. How do you decide how much of yourself to expose in your creative work?

I have an editor whose judgment aids me in this decision-making. There is comfort in knowing that what you initially put on a page will be read by a trusted individual with expertise in publishing before being released anywhere else. And you are disclosing to an individual reader who has done you the honor of buying the work.

What can you share with us about your writing process?

First, I think it's important for aspiring writers to understand that there’s nothing natural about being a writer. I am still working on a novel, going into my 6th year or so. Cutting for Stone took 8 years, the one before - 5 years. It’s hard to write, at least for me. Writing is revision. What you first lay out there is nothing. It’s just to get you warmed up. Fiction, which is my preferred genre and the genre in which I wrote my last book, Cutting for Stone, is successive layering of little brushstrokes here and there. You write a character, and you like him, but your editor doesn’t. You keep working until he suddenly turns into something lovable. I enjoy the process, but it’s not easy. Fortunately, I am in no hurry and I love my day job.

(Excerpt from Cutting for Stone )

How do you find time for writing?

I don’t. I would be more productive if I wrote full-time, but the fact that I can’t brings joy to the act of writing. I have to steal time: evenings, weekends, family time. It takes a bit of narcissism to be a writer. As a doctor, you always have an out: “Oh, sorry, I have to leave this baby shower/wedding/reunion/picnic... I have a patient.” You can’t say that as easily as a writer: “I’m sorry, I have to go upstairs. A character needs to be developed.” It’s a costly thing to be a writer. It is difficult even for people who love you to accept that kind of life.

What keeps you going?

Being a doctor. I love being a physician. I love the privilege of teaching the medical students, guiding their hands to feel the spleen for the first time. Let the spleen palpate your fingers. That’s priceless. If you teach them well, they’ll go on and teach thousands of their students, and their patients. Writing comes from this passion for doctoring.

If doctoring inspires writing, what does writing do for doctoring?

Writing gives permission to medical trainees to say, "This is how I was shocked by this, and this is how I felt." Not that every such sentiment needs to be read by anyone. There are a lot of stresses in medicine inherited from previous generations. Physicians have been trained to separate the emotional content from the intellectual content. If a person comes in with an axe in his head, your thoughts can't be on your emotions -- they're on airway, breathing, circulation. But after attending to the patient, one should return to addressing the emotional content of that experience. That's not something we were taught to do. Instead, we were basically trained to ignore our own emotional distress. It explains much of addiction, I think. Physicians don’t take drugs to produce euphoria; they take drugs to relieve the dysphoria of their own existence.

You believe that this is something that writing can heal?

Writing, like reading, taps into a different part of the brain. I would recommend it to everybody, because writing enables us to understand what we’re thinking. It’s very powerful to talk to yourself. I write in a journal often. I make myself do it: sit in a chair and try to write something, anything. And in that, insights come. It’s good therapy. It’s also not what you should subject the world or readers to, not even your spouse. It’s for you, to get your head straight.

What is your advice to medical trainees who aspire to a writing career?

First, I suggest you keep a journal, for your own consumption. If you write to publish, first make sure you have something to write about. Understand the genre you write in and the markets interested in publishing your type of work. You must meet a certain standard and respect the genre into which you’re trying to break. Secondly, read fiction. Through it, you practice making little movies in your head. It’s a powerful brain-building exercise: learning to hold a story in your mind, putting all the pieces together. Third, I don’t have any formula. Writing -- like medicine -- is difficult, but worth the effort.

What's the best thing about writing?

I love when, after all the hard work of writing and rewriting, I arrive at a point where it all seems to fit together, to make sense, to click. The moment when I realize that the story worked before anyone has had a chance to read it -- that’s what I will remember when I’m dying. Not interviews with NPR or comments on the backs of my books, but those moments when I was alone in front of my keyboard and white board and said: “Ah!” The muse spoke, the utter mystery of your right brain finding an answer that fits brain and heart, and the pieces -- click.